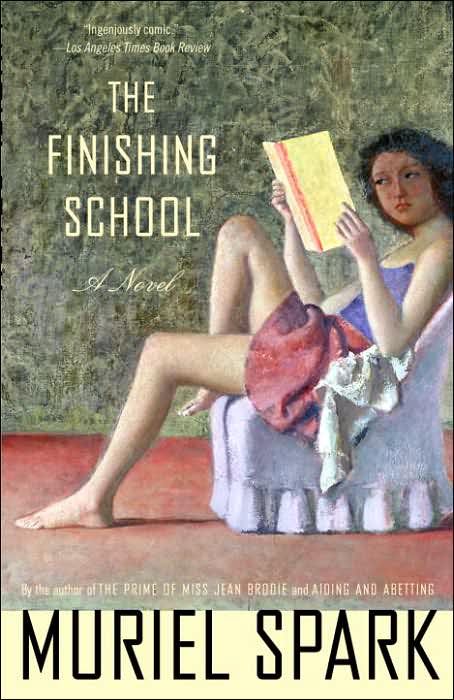

So begins Muriel Spark's last novel, The Finishing School,

a satiric look at a private progressive institution that Miss Jean Brodie in her prime would have been quick to deem a “crank” school and would have been loathe to be associated with.

a satiric look at a private progressive institution that Miss Jean Brodie in her prime would have been quick to deem a “crank” school and would have been loathe to be associated with.Rowland Mahler and his wife Nina Parker operate College Sunrise, a school where parents with “dire wealth” consent to send their teenagers for a year or two to get them out of the way. College Sunrise could not in any way compete with the famous schools and finishing establishments recommended by Gabbitas, Thring and Wingate in shiny colored brochures. Indeed, College Sunrise was almost unknown in the more distinctive educational circles, and in cases where it was known, it was frequently dismised as being rather shady. The fact that it moved house from time to time, that it seldom offered a tennis court and that its various swimming pools looked greasy, were the subject of gossip when the subject arose, but it was known that there had so far been no sexual scandals and that it was an advanced sort of school, bohemian, artistic, tolerant. What they smoked or sniffed was little different from the drug-taking habits of any other school, whether it be housed in Lausanne or in a street in Wakefield.

When the novel opens College Sunrise is in operation on the lake at Ouchy after previously being located in Brussels and Vienna. Nina conducts “casual afternoon comme il faut talks” with the school’s eight students ("'Be careful who takes you to Ascot,' she said, 'because, unless you have married a rich husband, he is probably a crook.'") while Rowland teaches creative writing. In fact, one of the students, 17-year-old Chris Wiley, red-haired, handsome, annoyingly self-assured, has enrolled in College Sunrise specifically so that he can write his historically inaccurate novel on Mary, Queen of Scots.

Rowland reads the opening pages of Chris' novel, finds them "quite good," and then experiences a debilitating case of writer's block where his own novel is concerned. Most of Spark's novel is thereafter concerned with the uneasy relationship between Rowland and Chris: Rowland's jealousy at first amuses Chris, who taunts Rowland with his hidden-away work-in-progress and thrives on reports that Rowland has been searching his belongings in a desperate attempt to find it. Later, after Nina is finally able to convince Rowland that his obsession with Chris' novel is bordering on insanity and he seeks a cure by temporarily checking into a monastery, Chris finds he requires Rowland's presence or else he is unable to write. Clearly, the madness goes both ways.

Nina wants Chris gone but realizes his tuition is needed less the school go under. She begins an affair with an art historian who lives in a neighboring villa. Rowland knows and doesn't care; he's busy attempting to sleep with the servant who is sleeping with Chris.

Nina, her lover, and the students all speculate whether Rowland's obsession with Chris' novel is actually a case of misplaced homosexual desire.

Finally, two of the publishers Chris has sent his novel to come to Ouchy and begin to offer a bit of perspective on Chris's talent and prospects. Chris' confidence is momentarily shaken, but he's quick to once again manipulate those around him, especially when he sees Rowland's chances at literary success wax considerably. I won't say who or how, but someone almost dies.

Now, while I loved The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, I remained largely indifferent to The Finishing School. I read it twice to see if I could put my finger on what kept it from being a more enjoyable, a more memorable read. The best I could come up with is that Spark’s natural inclination to omit all but of vital import undercut her efforts here. Chris and Rowland discuss whether they feel their characters take on a life of their own; Chris maintains that his are firmly under his control and can do nothing he does not will. Spark’s characters here definitely fall under strict authorial control; she pushes them about to advance her story without bringing them fully to life. And why she chose to have the character whose writing is called "actually a lot of shit" by a prospective publisher, who recognizes that Chris' approaching success is based on his youth, not his talent, be the one whose methods most mimic her own is definitely beyond my understanding.

I also thought that the use of flash forwards, which I am, in general, exceedingly fond of, and found most effective in Jean Brodie (and in The Driver's Seat, which I read last month), undercut my concern in The Finishing School. While knowing that Miss Brodie is to be betrayed, that Sandy will become a nun, that Mary will be killed in a fire (or that that strange Lise is going to be murdered before morning comes), heightens the suspense and keeps me engaged with how future events are to come about, foreknowledge here deflated my interest. Why should I care now about the state of Rowland and Nina's marriage when I know she's going to be much happier as an art historian married to someone else? Why should I care now that Chris' novel is no good if he's still going to manage to get it published? Why should I care now about any of the students at the Sunrise School when I know they all have enough money or family prestige to take the rough edges off their years to come?

Based on these two books, I'd have to say that if an author can't or isn't willing to vary her style and technique from book to book, she ought to take care that the stories she has to tell will work with her style rather than against it.

I'm late getting this posted compared to everyone else, so I'll wait to discuss Jean Brodie in the Metaxu Cafe forums. I will say I'm glad this Slaves of Golconda reading gave me reason to read it again--I read it back in high school and retained very little--and that I do intend to read more by Spark. I'm going to chose titles for the most part, though, from the first half of her career when her style is economical, but not yet miserly. I don't have a problem meeting a writer halfway, but I'm not willing to do more than that.

(cross posted at pages turned)

2 comments:

It's interesting that what is a strength in one book -- the economy of the language -- can quickly turn into a weakness in another. An author has to be careful with her/his quirks and interests and styles, so they don't take over and become overdone.

My response to The Finishing School was very similar to yours. It was the first Spark novel that I'd read in many years, and I was afraid afterwards that I had overestimated her. Perhaps on rereading her previous novels would strike me as being as thin as The Finishing School. Happily, now that I've begun rereading I've found that not to be the case. It's just The Finishing School that doesn't measure up.

Post a Comment